Passings: Gary Graver, Cinematographer and Director

One of the most important cinematic auteurs of the last 50 years passes away, and I'm woefully underequipped to expound. Go figure.

One of the most important cinematic auteurs of the last 50 years passes away, and I'm woefully underequipped to expound. Go figure.Director Robert Altman's influence looms large over modern cinema, so much so that eloquent testimonials to the man's work can be found all over the Blogosphere (here are two of my favorites). But my Altman experience extends to just four complete viewings: The Player (so universally loved and pungently witty it'd be redundant for me to cluck on about it), Popeye (still one of the oddest comic-to-film adaptations ever made, with Altman's very free-form style constantly fighting with a very structured cartoon universe), MASH (overrated, but not without its moments), and Buffalo Bill and the Indians (an erratic but interestingly off-kilter western that had me scratching my head as a kid). This means I haven't seen Nashville or McCabe and Mrs. Miller, widely reputed to be two of the finest films of the seventies (make that ever). They're on my Netflix cue, though, so don't lob too many eggs my way.

Altman took his journey to the Big Backlot in the Sky on November 20, but just four days earlier a much more obscure forty-year veteran of the film industry--Gary Graver--also passed away. I suppose it says something about me (God knows what) that Graver's body of work lives much nearer to my heart than Altman's.

Born in 1938 in Portland, Oregon, Gary Graver moved to California at age twenty to pursue an acting career. Despite studying with acknowledged masters like Jeff Corey and Lee J. Cobb, Graver dropped his thespian aspirations and segued into behind-the-scenes work in the early sixties. He honed his technical cinema chops with a two-year stint in the US Navy Combat Camera Group and began his career as a cinematographer in earnest after finishing his tour of duty.

In the late sixties Graver mustered up the chutzpah to approach Orson Welles for a gig. Welles, surprisingly, accepted him, and the two men enjoyed a decade-and-a-half as collaborators on several documentaries (and, most famously, Welles' 1973 feature F for Fake) before Welles' passing in 1985.

But it wasn't Graver's work with one of the world's greatest cinematic artists that made his name a fixture with me. Nor was it Graver's three decades of pseudonymous work as an adult-movie director (though a cursory scan of the man's IMDB directorial dossier reveals inspired titles like Cape Rear and One Million Heels BC). No, for me, Graver will always be the guy who lensed Al Adamson's most entertaining movies.

The wonderfully ramshackle genre efforts of Al Adamson easily merit a blog of their own. The micro-budget helmsman directed

several exploitation, action, and horror flicks throughout the 1960's and '70's, and he and his promotional wizard producer Sam Sherman frequently re-titled these epics multiple times to squeeze every last dime out of them on the flourishing drive-in circuit. Mainstream critics sneezed at the director's work (if they acknowledged it at all) back then, but Adamson's cheap productions made a tidy profit and (most importantly) entertained the hell out of moviegoers--myself most emphatically included.

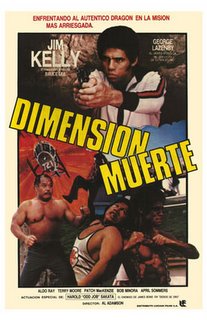

several exploitation, action, and horror flicks throughout the 1960's and '70's, and he and his promotional wizard producer Sam Sherman frequently re-titled these epics multiple times to squeeze every last dime out of them on the flourishing drive-in circuit. Mainstream critics sneezed at the director's work (if they acknowledged it at all) back then, but Adamson's cheap productions made a tidy profit and (most importantly) entertained the hell out of moviegoers--myself most emphatically included.Graver shot almost all of Adamson's movies, and I caught up with one of the few I hadn't seen over Thanksgiving weekend. 1977's Death Dimension stars Jim Kelly (Bruce Lee's afro-ed and ass-kicking bud in Enter the Dragon) as a superfly secret agent who works to thwart Harold 'Oddjob' (yes, that Oddjob) Sakata's sale of a deadly 'Freeze Bomb' on the international black market. It's a fun-filled attempt at James Bond thrills on a K-Mart budget, and Graver's recent passing brought his specific contributions into sharp focus for me as I watched. The framing and composition of some of the action scenes--in particular, an imaginative shootout between a single-engine plane and a mountain cable car--nearly knocked my socks off, especially given the pennies that Adamson and Graver likely worked with.

After the movie ended I started musing about some of my favorite moments in Al Adamson's

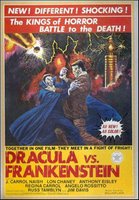

filmography--a spooky acid freakout from 1971's Dracula vs. Frankenstein; the disorienting vampire close-ups in Horror of the Blood Monsters; and the sweltering pursuit scene at the end of Satan's Sadists, among others. I'd been watching Adamson's movies since the age of eight, and for the first time I realized how deeply my enjoyment of them was rooted in Graver's lenswork--equal parts classroom-hygeine-movie-verite and rock-'em-sock-'em frenetic. Thank you kindly, Mr. Graver.

filmography--a spooky acid freakout from 1971's Dracula vs. Frankenstein; the disorienting vampire close-ups in Horror of the Blood Monsters; and the sweltering pursuit scene at the end of Satan's Sadists, among others. I'd been watching Adamson's movies since the age of eight, and for the first time I realized how deeply my enjoyment of them was rooted in Graver's lenswork--equal parts classroom-hygeine-movie-verite and rock-'em-sock-'em frenetic. Thank you kindly, Mr. Graver.Conventional wisdom would shy away from labelling Gary Graver an artiste, but he did memorable work--on a (literal) dime, in some of the cheapest, most

widely-ridiculed movies in cinema history. That's a triumph over adversity; a legacy worthy (in these eyes, at least) of celebration. And though their careers couldn't have been more divergent, I can only imagine the great showbiz war stories he and Altman are sharing now.

widely-ridiculed movies in cinema history. That's a triumph over adversity; a legacy worthy (in these eyes, at least) of celebration. And though their careers couldn't have been more divergent, I can only imagine the great showbiz war stories he and Altman are sharing now.

Comments