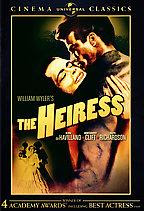

The Heiress: Dysfunctionality in Period Finery

Think old black and white movies can't speak cold hard truths that still register today? Then take a look at The Heiress, director William Wyler's 1949 tragic costume drama (out recently on DVD). Beneath its genteel nineteenth-century surface beats the most bracingly caustic--and brutally honest--of hearts.

Think old black and white movies can't speak cold hard truths that still register today? Then take a look at The Heiress, director William Wyler's 1949 tragic costume drama (out recently on DVD). Beneath its genteel nineteenth-century surface beats the most bracingly caustic--and brutally honest--of hearts.The story proper follows the path of Catherine Sloper (Olivia DeHavilland), a plain and unexceptional young woman whose father Austin (Ralph Richardson) happens to be a wealthy physician. One night Catherine is pulled away from her routine of needlepoint and isolation to attend a lavish society party, and the drab heiress makes the acquaintance of dashing ne'er do well Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift). Soon Morris is courting her fervently, a pursuit that inspires suspicion in her father even as it brings Catherine out of her shell.

If all of this sounds like the preamble to a typical period weeper, rest assured that it ain't. Wyler--one of the studio era's least-showy directors and also one of its best with actors--eschews over-the-top dramatics until the end, and wisely keeps things honed in sharply on the characterizations.

The ensemble responds with uniformly excellent work. DeHavilland received an Oscar for her performance here, and she's certainly good, but the real revelations surface within the supporting cast. Richardson always played stalwart gentlemen gracefully, and it's a revelation to see him really craft a sympathetic character from a potentially thankless and unlikeable role. The emotional aloofness and regret that subsume his genuine love for his daughter feel positively contemporary. Clift's vulnerability, meanwhile, imbues Townsend with genuine sweetness, and makes the character's intentions that much harder to read. Miriam Hopkins, endearing and nuanced as Catherine's well-intentioned aunt, rounds the cast out nicely.

Great as the actors are, though, it's the ending that floored me (and will likely do so to many modern viewers). It comes without a hint of the romanticized self-sacrifice or inspirational musical accompaniment that Hollywood movies normally use to obscure a downbeat climax. I won't drop any spoilers, but the conclusion here--that sometimes, no amount of love or penance can heal the emotional agonies loved ones can wreak upon one another--comes with quiet inevitability. It's a sobering--but refreshingly candid--finale, one that'd likely stand a snowball's chance in hell of getting greenlit by a major studio today.

Comments